Of all the places you can spend money in a tech company, the engineering team is often by far the largest cost-centre. Similar to digital ads, it’s also a place where, if you aren’t careful, you can waste a lot of money.

If less is more, think how much more more would be

When you’re trying to grow a new product, it’s the obvious place to start when you want to go faster. You want more customers and more revenue; the natural first place your mind lands is more features. Who doesn’t want more things? But to deliver more, you’re going to need more people.

Sure, more engineers mean more cost, but how else are you going to get everything you want shipped? It is a great feeling to see everyone super busy, cranking out lines of code and shipping features like there’s no tomorrow. This is what a high performing team looks like. Our velocity is through the roof! But hold on for a moment there. Since when did the quantity of output mean anything? Going fast is not a destination.

Fix your leaky bucket

Sadly, you can add 100, or 1000 engineers or designers or anyone else for that matter. You will then have an even longer list of things you absolutely must ship. More importantly, you are just burning cash. Just like a startup trying to grow rapidly by throwing money at ads, doubling down on acquisition, without giving a second thought to retention. Sure your acquisition numbers will look good, but you’ll retain naff all, and your costs will pass right through your bucket and out through the gaping hole in the bottom.

If you don’t have an engine that can reliably turn $1 into $2, think twice about meaningfully increasing your burn rate.

If what you build is not well targeted, does not solve a core need, then it’s the same as the leaky bucket - money spent without return. There’s no use saying it’s an investment for the future if you aren’t observing a key metric moving in the right direction

Long term costs v short term costs

Adding another member to the team is a permanent cost. It amazes me how much more willing management teams are to hire new people than spend a few hundred dollars on a piece of software to help the team do their job. Or have an engineer spend a couple of days manually implementing something instead of just buying it. When you consider the maintenance cost, it’s even more ridiculous.

More is not more

It’s an attractive fallacy, but it is a fallacy. Just because you are shipping lots of shiny new things, it doesn’t mean anything unless what you ship is valuable. More often than not, shipping less would get you further. If each new line of code, each new feature doesn’t help move your customers closer to achieving their goals faster or more thoroughly, then it is time wasted. If you built something nobody wants, you might as well have stayed in bed. It’s worth caveating that it is fine to ship the wrong thing if that is in service of learning what the right thing is. Expect to make missteps, but try to limit the investment they need.

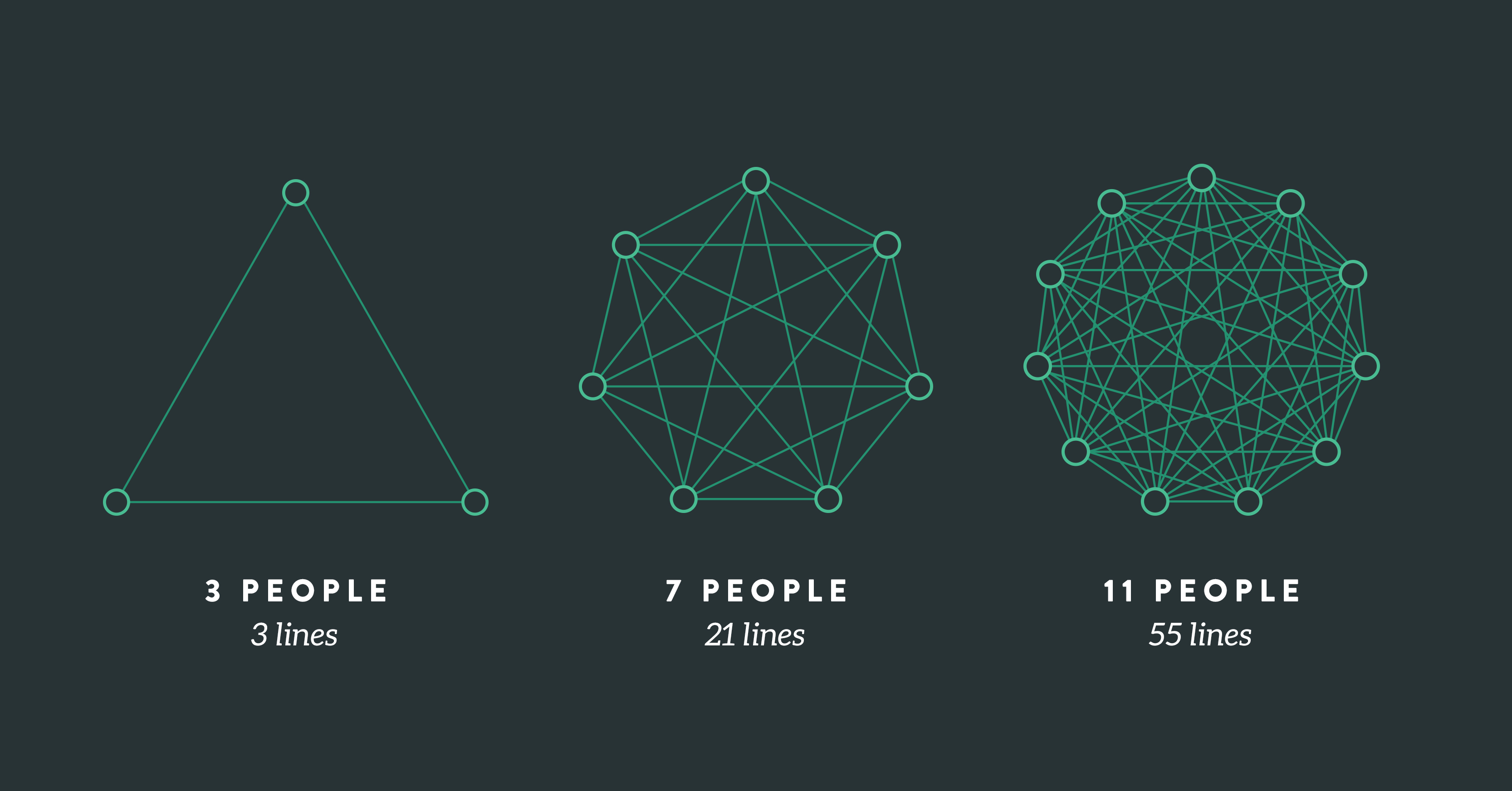

Communication complexity

Small teams have an incredibly low communication burden, with a team of two or three, everyone is within immediate reach. A consensus can be reached quickly, and ongoing debates to satisfy a room full of egos shouldn’t come into it. The more people you add, the more obfuscation happens, the further the team are from the real problems. More management burden, more planning time, more meetings. The longer you can resist this, the better.

Small but mighty

The good news is, you can achieve a lot with a few people. Below are a few examples of teams that have achieved incredible feats with surprisingly small teams.

As of last month, Notion had more than 1M users, all with just eighteen full-time employees. Not engineers, employees. Superhuman raised $33M at a valuation of $280M in May, has just 10 engineers. Even Basecamp, a 20-year-old company only has around 50 employees. They have over 3M accounts.

These aren’t simplistic products either, but they are all laser-focused on solving real problems their users have.

How to do it

Make bets, you’re not expected to get everything right

Randomness and chance still play a massive part in any success you may have, however well researched and prepared you are. This is fine; you have to embrace it. By making bets on what you believe to be the best way forward, you limit your exposure to risk. If you only spend two weeks on an experiment to test appetite for a specific feature, if it bombs, you haven’t wasted much time. If you go full steam ahead and drop six months of development effort into delivering all the bells and whistles, you have a huge exposure. You have zero guarantee that the effort was worth it.

Record your decisions and goals, reflect and improve

It’s all very well to experiment, but how do you know when your experiment has yielded results you can be confident in to build on? It’s hard, there’s no getting away from that. But by writing down your intentions, what you hope to build, what it should achieve, the investment needed, and how you’re going to measure success, you have a guide. Don’t stop here, if you don’t reflect on whether you met your goals after you launched and again after your feature has been in the wild for a month or so, you won’t be much further ahead than the blind feature machines.

When is it safe to grow

This isn’t to say never increase the size of your engineering team. Far from it. But if you are going to, make sure that you have a strong indication that the time and money invested has a high probability of making a return and getting you and your customers closer to achieving your goals. Once you’ve fixed the leaky bucket, you can then fill it up with water. Or engineers. Or whatever you want.

Source:

Source:

Source:

Source: